Share Investor note:

This article was published yesterday after much too ing and fro ing.

It was included here at Share Investor for one reason.

I believe it gives weight behind the argument that A1 vs A2 milk and I will leave it up to the reader to decide which way they believe.

Its inclusion on this blog is to do with the financial possibilities this sort of "research" has.

I'm not a big milk drinker of either A1 or A2 milk.

I'm neither a holder in any stock to do with this story.

The content, formatting and supporting links are shown as originally agreed with The Conversation and reflect the prior input of one of their editors. This article can be freely republished, with acknowledgements as to source [https://keithwoodford.wordpress.com].

Early evidence of an association between type 1 diabetes and a protein in cow milk, known as A1 beta-casein, was published in 2003. However, the notion that the statistically strong association could be causal has remained controversial.

As part of a seven-person team, we have reviewed the overall evidence that links A1 beta-casein to type 1 diabetes. Our research brings forward new ways of looking at that evidence.

Type 1 diabetes is the form of diabetes that often manifests during childhood. The key change is an inability of the pancreas to produce insulin, which is essential for transporting glucose across internal cell membranes.

There is common confusion between type 1 and the much more common type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system attacks the body’s own cells. Insulin-producing cells in the pancreas are then destroyed by “friendly fire”.

There is no accepted lifestyle change that will prevent or cure type 1 diabetes and daily insulin injections are required throughout life.

In contrast, people who develop type 2 diabetes still produce some insulin, but the liver and muscles become resistant to insulin’s ability to move glucose out of the blood and into the tissues. Type 2 diabetes is primarily a disease of middle-aged and older people and is related to excess weight, diet and lack of physical activity.

If A1 beta-casein is indeed triggering type 1 diabetes, then this would be of profound importance. Globally, there are approximately 78,000 new cases diagnosed in young people every year, with many additional cases diagnosed in adults.

Cows of European origin are the only source of A1 beta-casein. It is the result of a mutation, probably some thousands of years ago. Some of these cows produce beta-casein that is all A1, others produce a mix of A1 and another type known as A2, and others produce only the A2 type.

Goats, sheep, Asian cattle, buffalo, camels and indeed humans produce milk only of the A2 type.

A1 beta-casein, on digestion, releases a peptide (protein fragment) which has opioid and inflammatory characteristics. The protein fragment is called beta-casomorphin-7 (“caso” from casein, “morphin” from morphine-like, and 7 to indicate the fragment contains seven amino acids).

The release of this protein fragment is accepted science; it is the implications that have been controversial. There is scientific literature that links A1 beta-casein to multiple health conditions, but here, we restrict ourselves to type 1 diabetes.

The evidence in our paper comes from 71 studies covering population epidemiology, animal trials, in vitro laboratory experiments, biochemistry and pharmacology. Our assessment is that the evidence is highly suggestive that A1 beta-casein is associated with the onset of type 1 diabetes, but proof remains elusive. There have been no clinical trials specifically investigating a long-term diet free of A1 beta-casein.

Such trials would be very expensive and difficult, but not impossible, to conduct. People who are genetically susceptible to developing type 1 diabetes would need to be identified at birth and half of them randomly allocated to a diet free of A1 beta-casein for many years.

Clinical trials are very powerful when the effects are quickly evident. However, they are seldom practical when outcomes are caused by prolonged exposure to a particular food or other environmental factor, and where effects may take many years to manifest.

In these situations, other methods based on epidemiology, often combined with insights about biological mechanisms, provide the underpinnings for public health actions.

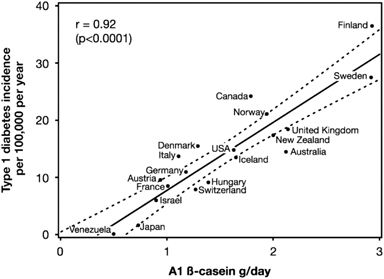

Studies across countries show very high correlations between type 1 diabetes incidence (with a variation of 280-fold) and intake of A1 beta-casein (more than five-fold variation).

In our paper, we report recent evidence from China where type 1 diabetes was almost unknown in the past. Now, it is increasing rapidly along the developed eastern seaboard. There is published data for two cities.

In Shanghai, the incidence (new cases) increased at 14.2% compound rate each year between 1997 and 2011. In Zhejiang (a major city south of Shanghai) it increased at 12% percent compound rate per annum between 2007 and 2013. These increases are mirrored by China’s increased per capita dairy consumption from 6kg in 1992 to 18kg in 2006, and with further substantial increases thereafter. There are no other apparent explanations for this rapid rise in Type 1 diabetes in China.

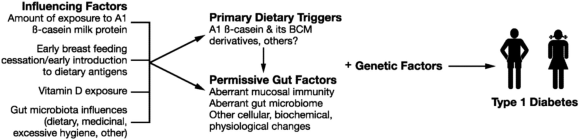

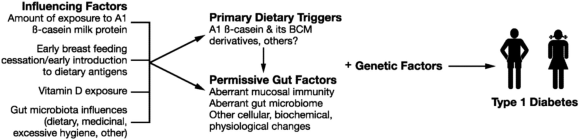

While A1 beta-casein may be the primary causal agent, there are probably many predisposing factors. A genetic predisposition has been known for some time but other factors such as infections and antibiotics which affect the intestinal mucosal barrier may prime the immune system to turn against the body. Inadequate Vitamin D levels may also be predisposing in some situations, although the evidence for this is limited.

Figure 2: Proposed Type 1 diabetes mechanisms (Source: here )

Figure 2: Proposed Type 1 diabetes mechanisms (Source: here )

It is feasible to breed all dairy herds to produce milk free of A1 beta-casein. The catch is that it would take at least ten years in most countries, even if all dairy farmers used only A2 bulls and A2 semen in breeding programmes from now on.

However, cow milk free of A1 beta-casein is increasingly available in many Western countries, including New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Britain. Goat and sheep milks are other options for those seeking milk that is free of A1 beta-casein.

In the absence of definitive proof, consumers have to make their own choices. This is particularly important in situations where there is a family history of type 1 diabetes. However, the increasing incidence means that type 1 diabetes is increasingly showing up in families without that prior family history, and this is particularly relevant to parents of infants and young children.

An open access version of the research is available here.

Boyd Swinburn is Professor of Population Nutrition and Global Health at Auckland University. He was commissioned in 2004 by the New Zealand Food Safety Authority to review the health evidence at that time relating A1 and A2 beta-casein. That report is available at

http://biochemie-crashkurs.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Betacasein.pdf

He has no other disclosures relevant to beta-casein issues.

Keith Woodford holds an honorary position as Professor of Agri-Food Systems at Lincoln University (i.e., retired but still active academically). He consults for but remains independent of a range of agri-food companies, some of whom have interests in issues of beta-casein. He authored the book ‘Devil in the Milk’, published in 2007 in New Zealand (Craig Potton Publishing, now Potton and Burton), with an American version published in 2009 (Chelsea Green), and an updated NZ/Australian version in 2010 (Potton and Burton). He writes regularly on beta-casein issues at https://keithwoodford.wordpress.com . He has co-authored five peer-reviewed papers in international science and nutrition journals on beta-casein issues. He has no shareholding in any dairy company.

This article was published yesterday after much too ing and fro ing.

It was included here at Share Investor for one reason.

I believe it gives weight behind the argument that A1 vs A2 milk and I will leave it up to the reader to decide which way they believe.

Its inclusion on this blog is to do with the financial possibilities this sort of "research" has.

I'm not a big milk drinker of either A1 or A2 milk.

I'm neither a holder in any stock to do with this story.

[The article below was intended to be published some weeks back at The Conversation. The Conversation is the online portal, funded by Universities in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, where academics are encouraged to communicate and converse with non-academics. However, this particular article was blocked at the last minute by the Senior Editor(s) at The Conversation, having previously been approved within their editorial system. The Senior Editor(s) felt that the interests of associated commercial parties, who might benefit from dissemination of the article, were too great. A fuller story of that publishing saga will be posted shortly.

The content, formatting and supporting links are shown as originally agreed with The Conversation and reflect the prior input of one of their editors. This article can be freely republished, with acknowledgements as to source [https://keithwoodford.wordpress.com].

Authors: Keith Woodford & Boyd Swinburn

Disclosures: See end of article

Disclosures: See end of article

Type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks its own insulin-producing cells, is on the rise globally.

Early evidence of an association between type 1 diabetes and a protein in cow milk, known as A1 beta-casein, was published in 2003. However, the notion that the statistically strong association could be causal has remained controversial.

As part of a seven-person team, we have reviewed the overall evidence that links A1 beta-casein to type 1 diabetes. Our research brings forward new ways of looking at that evidence.

Different types of diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is the form of diabetes that often manifests during childhood. The key change is an inability of the pancreas to produce insulin, which is essential for transporting glucose across internal cell membranes.

There is common confusion between type 1 and the much more common type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system attacks the body’s own cells. Insulin-producing cells in the pancreas are then destroyed by “friendly fire”.

There is no accepted lifestyle change that will prevent or cure type 1 diabetes and daily insulin injections are required throughout life.

In contrast, people who develop type 2 diabetes still produce some insulin, but the liver and muscles become resistant to insulin’s ability to move glucose out of the blood and into the tissues. Type 2 diabetes is primarily a disease of middle-aged and older people and is related to excess weight, diet and lack of physical activity.

A1 beta-casein comes from European-type cows

If A1 beta-casein is indeed triggering type 1 diabetes, then this would be of profound importance. Globally, there are approximately 78,000 new cases diagnosed in young people every year, with many additional cases diagnosed in adults.

Cows of European origin are the only source of A1 beta-casein. It is the result of a mutation, probably some thousands of years ago. Some of these cows produce beta-casein that is all A1, others produce a mix of A1 and another type known as A2, and others produce only the A2 type.

Goats, sheep, Asian cattle, buffalo, camels and indeed humans produce milk only of the A2 type.

A1 beta-casein, on digestion, releases a peptide (protein fragment) which has opioid and inflammatory characteristics. The protein fragment is called beta-casomorphin-7 (“caso” from casein, “morphin” from morphine-like, and 7 to indicate the fragment contains seven amino acids).

The release of this protein fragment is accepted science; it is the implications that have been controversial. There is scientific literature that links A1 beta-casein to multiple health conditions, but here, we restrict ourselves to type 1 diabetes.

Evidence but no definitive proof

The evidence in our paper comes from 71 studies covering population epidemiology, animal trials, in vitro laboratory experiments, biochemistry and pharmacology. Our assessment is that the evidence is highly suggestive that A1 beta-casein is associated with the onset of type 1 diabetes, but proof remains elusive. There have been no clinical trials specifically investigating a long-term diet free of A1 beta-casein.

Such trials would be very expensive and difficult, but not impossible, to conduct. People who are genetically susceptible to developing type 1 diabetes would need to be identified at birth and half of them randomly allocated to a diet free of A1 beta-casein for many years.

Clinical trials are very powerful when the effects are quickly evident. However, they are seldom practical when outcomes are caused by prolonged exposure to a particular food or other environmental factor, and where effects may take many years to manifest.

In these situations, other methods based on epidemiology, often combined with insights about biological mechanisms, provide the underpinnings for public health actions.

Type 1 diabetes varies between countries

Studies across countries show very high correlations between type 1 diabetes incidence (with a variation of 280-fold) and intake of A1 beta-casein (more than five-fold variation).

Figure 1: Correlation between A1 β-casein supply per capita in 1990 and type 1 diabetes incidence (1990–1994) in children aged 0–14 years in 19 countries. Original source here

Such country-level studies are sometimes criticised because statistical associations between populations do not necessarily apply at the individual level. However, the A1 beta-casein results are very stable in that they are not dependent on one or two outlier countries and no-one has come up with an alternative explanation as to what could explain such very high correlations.

In our paper, we report recent evidence from China where type 1 diabetes was almost unknown in the past. Now, it is increasing rapidly along the developed eastern seaboard. There is published data for two cities.

In Shanghai, the incidence (new cases) increased at 14.2% compound rate each year between 1997 and 2011. In Zhejiang (a major city south of Shanghai) it increased at 12% percent compound rate per annum between 2007 and 2013. These increases are mirrored by China’s increased per capita dairy consumption from 6kg in 1992 to 18kg in 2006, and with further substantial increases thereafter. There are no other apparent explanations for this rapid rise in Type 1 diabetes in China.

Bovine milk has previously been identified as a potential risk factor for Type 1 diabetes. There have been multiple trials comparing breast milk to formula, and also comparing alternative ages of first introduction to bovine milk. But clear answers have been elusive.

Those inconsistent results are not surprising if the problem is indeed A1 beta-casein, which has such variability of levels between countries. None of these trials have specifically compared A1 beta-casein to A2 beta-casein, and none of the trial treatments have been long term post-weaning. In essence, these trials have lacked the necessary specificity.

Those inconsistent results are not surprising if the problem is indeed A1 beta-casein, which has such variability of levels between countries. None of these trials have specifically compared A1 beta-casein to A2 beta-casein, and none of the trial treatments have been long term post-weaning. In essence, these trials have lacked the necessary specificity.

Predisposing factors

While A1 beta-casein may be the primary causal agent, there are probably many predisposing factors. A genetic predisposition has been known for some time but other factors such as infections and antibiotics which affect the intestinal mucosal barrier may prime the immune system to turn against the body. Inadequate Vitamin D levels may also be predisposing in some situations, although the evidence for this is limited.

Figure 2: Proposed Type 1 diabetes mechanisms (Source: here )

Figure 2: Proposed Type 1 diabetes mechanisms (Source: here )

It is clear that none of the multiple predisposing factors are capable of being causal by themselves; instead they create the environment where a trigger can do its damage. Accordingly, the key is to remove either the trigger or all the predisposing factors. When predisposing factors are multiple, it is usually easiest to remove the key trigger.

Public health and personal choice

It is feasible to breed all dairy herds to produce milk free of A1 beta-casein. The catch is that it would take at least ten years in most countries, even if all dairy farmers used only A2 bulls and A2 semen in breeding programmes from now on.

However, cow milk free of A1 beta-casein is increasingly available in many Western countries, including New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Britain. Goat and sheep milks are other options for those seeking milk that is free of A1 beta-casein.

In the absence of definitive proof, consumers have to make their own choices. This is particularly important in situations where there is a family history of type 1 diabetes. However, the increasing incidence means that type 1 diabetes is increasingly showing up in families without that prior family history, and this is particularly relevant to parents of infants and young children.

An open access version of the research is available here.

****

Disclosures

Disclosures

Boyd Swinburn is Professor of Population Nutrition and Global Health at Auckland University. He was commissioned in 2004 by the New Zealand Food Safety Authority to review the health evidence at that time relating A1 and A2 beta-casein. That report is available at

http://biochemie-crashkurs.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Betacasein.pdf

He has no other disclosures relevant to beta-casein issues.

Keith Woodford holds an honorary position as Professor of Agri-Food Systems at Lincoln University (i.e., retired but still active academically). He consults for but remains independent of a range of agri-food companies, some of whom have interests in issues of beta-casein. He authored the book ‘Devil in the Milk’, published in 2007 in New Zealand (Craig Potton Publishing, now Potton and Burton), with an American version published in 2009 (Chelsea Green), and an updated NZ/Australian version in 2010 (Potton and Burton). He writes regularly on beta-casein issues at https://keithwoodford.wordpress.com . He has co-authored five peer-reviewed papers in international science and nutrition journals on beta-casein issues. He has no shareholding in any dairy company.